If the dynamics of the population is subject to the demographic variation only, then the growth dynamics is governed by

Estimation of Parameters

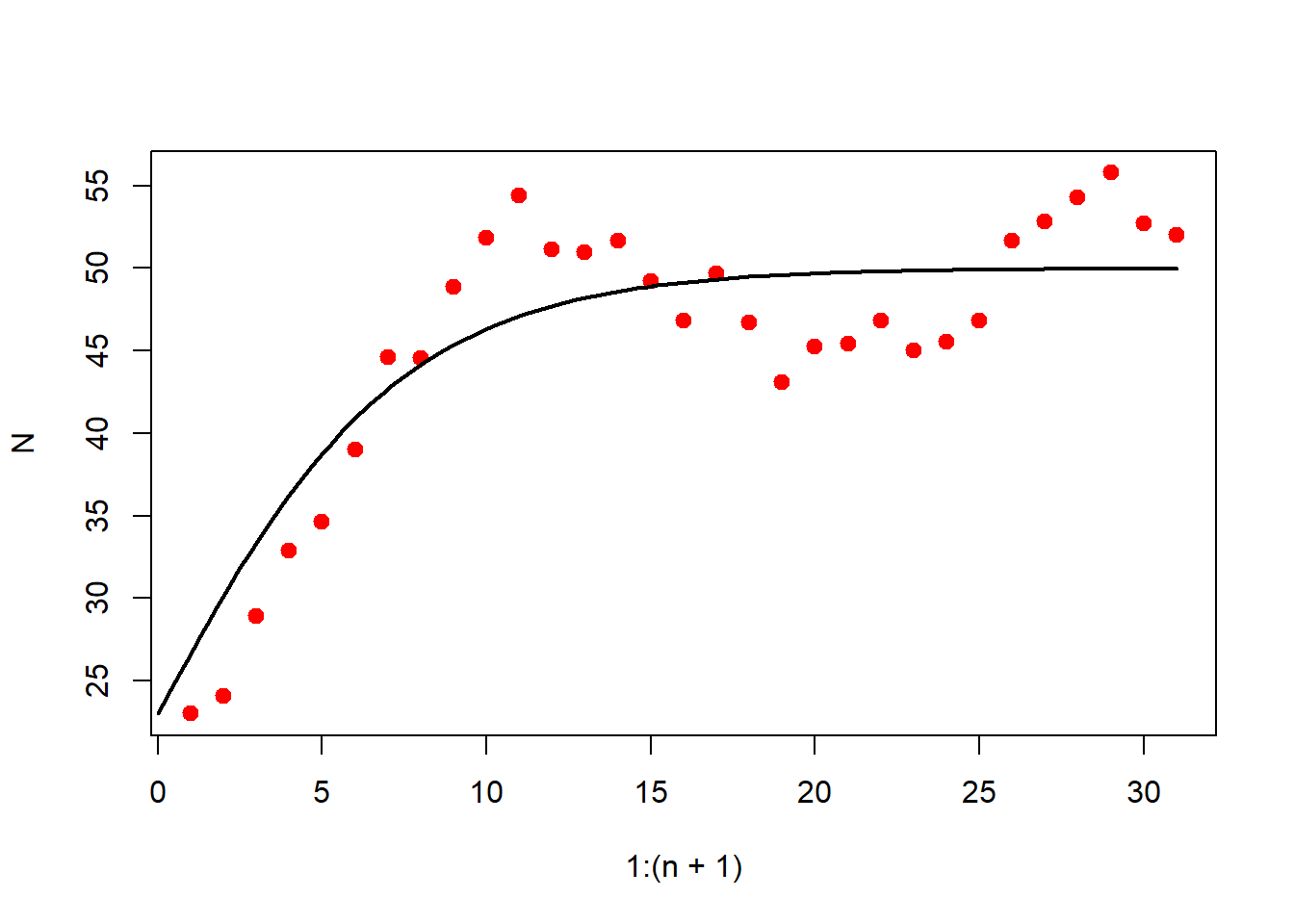

Consider \(\{ N_1,N_2,\cdots,N_{n+1}\}\) be the observed time series data. The absolute change in population size at time \(t\) is approximated as \[\frac{\mathrm{d}N(t)}{\mathrm{d}t} \approx \frac{N(t+\Delta t)-N(t)}{\Delta t}.\] We assume the yearly changes in population size, so that \(\Delta t=1\). The relative changes in population sizes is given by

\[\begin{equation}

R(t) = \frac{1}{N}\frac{\mathrm{d}N(t)}{\mathrm{d}t} = \frac{\mathrm{d}}{\mathrm{d}t} \log N \approx \log N(t+1)- \log N(t).

\end{equation}\]

So, for a given population time series data of size \(n+1\), we have \(n\) many observed per capita growth rates \(\{R(1),R(2),\cdots,R(n)\}\). We would like to investigate the dynamics of the population when it is subject to environmental stochastic perturbations alone. The following stochastic differential equation has been used to describe to population changes that is exposed to environmental variability.

\[\begin{equation}\label{eq:theta logistic}

\mathrm{d}N = r_m N(t) \left[ 1-\left( \frac{N(t)}{K}\right)^{\theta} \right]\mathrm{d}t + \sigma_{e} N(t)\mathrm{d}W(t) ,

\end{equation}\]

where \(\sigma_{e}\) represents the intensity of the stochastic perturbation and \(W(t)\) is the one dimensional Brownian motion which satisfies \(\mathrm{d}W(t) \approx W(t+\mathrm{d}t)-W(t) \sim \mathcal{N}(0,\mathrm{d}t)\). Our goal is to estimate the parameters of the stochastic model by employing Bayesian statistical methods. First we compute the likelihood function of the model parameters given the population size. It is to be noted that the likelihood function can be written either by conditional on the population size \(\{N_t\}\) or on the growth rates \(\{R_t\}\). We can use the either observations on \(\{R_t\}\) or \(\{N_t\}\) to obtain the posterior distribution of the model parameters. Now, we shall write down the likelihood function given the population time series. Using the equation \(\eqref{eq:theta logistic}\) and utilizing the distributional assumptions, we see that the absolute changes in the population size, conditional on the current size, is normally distributed. So we obtain the following (assuming \(\Delta t =1\)):

\[\begin{align}

N(t+1)-N(t)|N(t) &\sim \mathcal{N}\left(r_m N(t) \left[ 1-\left( \frac{N(t)}{K}\right)^{\theta} \right], \sigma_{e}^2 N(t)^2 \right) \notag \\

\frac{N(t+1)-N(t)}{N(t)}| N(t) &\sim \mathcal{N}\left(r_m \left[ 1-\left( \frac{N(t)}{K}\right)^{\theta} \right], \sigma_{e}^2 \right) \notag \\

N(i+1)-N(i) &\sim \mathcal{N}\left(r_m N(i)\left[1-\left( \frac{N(i)}{K}\right)^{\theta} \right], \sigma_{e}^2 N(i)^2 \right) \notag \\

N(i+1)|N(i) &\sim \mathcal{N}\left(N(i) + r_m N(i)\left[1-\left( \frac{N(i)}{K}\right)^{\theta} \right], \sigma_{e}^2 N(i)^2 \right) \label{eq:N_i}

\end{align}\]

We can estimate the parameters using (\(\ref{eq:N_i}\)) using the method of maximum likelihood. Therefore by using (\(\ref{eq:N_i}\)), our goal is to estimate parameters \(r_m\), \(\theta\), \(K\), \(\sigma_e^2\). If we use \(R_t\) values, then the following equation will be used for computation of the likelihood.

\[\begin{equation}

R(t)|N(t) \sim \mathcal{N}\left(r_m\left[1-\left( \frac{N(t)}{K}\right)^{\theta} \right],\sigma_{e} ^2\right) \label{eq:R_T},

\end{equation}\] so that the log-likelihood function will be,

\[\begin{equation}\label{eq:likelihood}

\mbox{likelihood} = -\frac{n}{2}\log(2\pi)-\frac{n}{2}\log(\sigma_e^2)-\frac{1}{2\sigma_e^2}\sum_{i=1}^{n}\left\lbrace R(i)- r_m\left[1-\left( \frac{N(i)}{K}\right)^{\theta}\right] \right\rbrace^2 .

\end{equation}\]

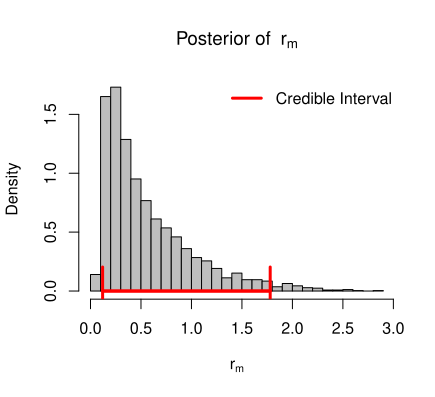

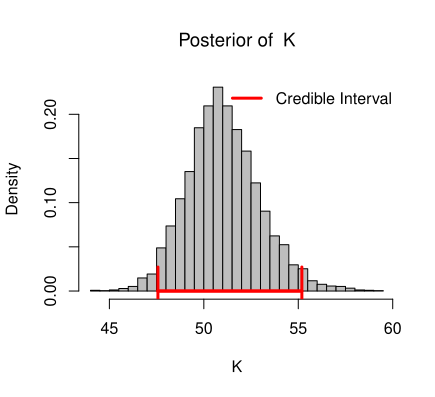

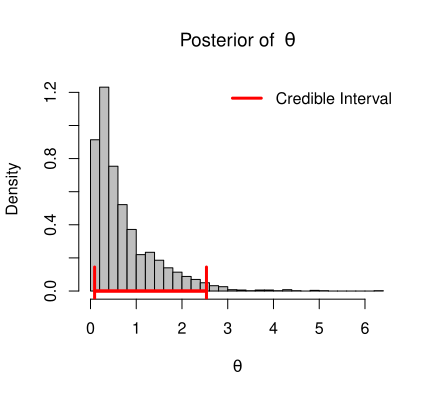

To draw inference about \(r_m\), \(\theta\), \(K\) and \(\sigma_e^2\), we consider inverted gamma prior for variance term \(\sigma_e^2\), gamma prior for \(\theta\), normal prior for \(K\) and normal prior for \(r_m\). Then the complete Bayesian model for this data can be written as,

\[\begin{align*}

N(i+1)|N(i),r_m,\theta,K,\sigma_e^2 &\sim \mathcal{N}\left(N(i) + r_m N(i)\left[1-\left( \frac{N(i)}{K}\right)^{\theta} \right], \sigma_{e}^2 N(i)^2 \right) \\

r_m|\alpha_0,\beta_0 &\sim \mathcal{N}(\alpha_0,\beta_0)\\

K| \mu_K,\sigma_K^2 &\sim \mathcal{N}(\mu_K,\sigma_K^2)\\

\theta|\alpha_1,\beta_1 &\sim \mathcal{G}(\alpha_1,\beta_1) \\

\sigma_e^2|\alpha_2,\beta_2 &\sim \mathcal{IG}(\alpha_2,\beta_2),

\end{align*}\]

where \(\alpha_0,\alpha_1,\alpha_2,\beta_0,\beta_1,\beta_2,\mu_K\), and \(\sigma_K^2\) are hyper-parameters and assumed to be known. As the starting population size is known, \(P(N(1)=N_0)=1\). We take \(N(1)=N_0\) as the starting population size and assumed to be a fixed quantity. The joint posterior distribution of \(r_m,\theta,K,\sigma_e^2\) can be written as,

\[\begin{equation*}

f(r_m,\theta,K,\sigma_e ^2|\boldsymbol{N})=\frac{f(\boldsymbol{N},r_m,\theta,K,\sigma_e ^2)}{f_{\boldsymbol{N}}(\boldsymbol{N})},

\end{equation*}\] where \(\boldsymbol{N}=(N(1),N(2),\cdots,N(n+1))'\) represents the data and \(f_{\boldsymbol{N}}(\boldsymbol{N})\) is the marginal distribution of \(\boldsymbol{N}\).

\[\begin{equation}\label{eq:27}

f\left(r_m,\theta,K,\sigma_e^2|\boldsymbol{N}\right) = \frac{f\left(\boldsymbol{N}|r_m,\theta,K,\sigma_e^2\right)\cdot f\left(r_m,\theta,K,\sigma_e^2\right)}{f(\boldsymbol{N})}.

\end{equation}\] We assume that \(r_m,\theta,K,\sigma_e^2\) are independent variables, therefore \(f(r_m,\theta,K,\sigma_e ^2)\) can be written as,

\[\begin{equation}

f\left(r_m,\theta,K,\sigma_e^2\right)=f(r_m)\cdot f(\theta) \cdot f(K) \cdot f\left(\sigma_e^2\right).

\end{equation}\] So, equation (\(\ref{eq:27}\)) becomes, \[\begin{eqnarray*}

f\left(r_m,\theta,K,\sigma_e^2|\boldsymbol{N}\right) &\propto& f\left(\boldsymbol{N}|r_m,\theta,K,\sigma_e^2\right)\cdot f\left(r_m,\theta,K,\sigma_e^2\right) \\

&\propto& f(\boldsymbol{N}|r_m,\theta,K,\sigma_e ^2)\cdot f(r_m)\cdot f(\theta) \cdot f(K) \cdot f(\sigma_e ^2)~~[\mbox{independence of priors}] \\

&\propto& \left[\prod_{i=1}^{n} f\left(N(i+1)|N(i)\right)\right]\cdot f(r_m)\cdot f(\theta) \cdot f(K) \cdot f(\sigma_e ^2).

\end{eqnarray*}\]

The right hand side of the above expression is product of the likelihood and the prior, which is nothing but unnormalized joint posterior distribution of parameters. Since, the distribution does not follow some common known distribution, we use the Gibbs sampling method that simulates samples from the conditional distribution. So we generate random sample from conditional posterior distribution of each parameters. However, it is observed that in this case also the conditional posterior does not follow any known distribution. So, we use grid approximation algorithm to approximate the posterior probability distribution.

Let \(\boldsymbol{\beta} = \left(r_m,\theta, K, \sigma_e^2\right)\). Since, \(N(i)\)’s are not independent, so the likelihood can be written as,

\[\begin{eqnarray*}

\mbox{likelihood} &=& f\left(N(1),N(2),\cdots , N(n+1) ; \beta \right) \\

&=& f\left(N(n+1)|N(n) ; \beta \right)\cdot f\left(N(n)|N(n-1) ; \beta \right) \cdots f\left(N(2)|N(1) ; \beta \right)\cdot f\left(N(1) ; \beta \right) \\

&=& \prod_{i=1}^{n} f\left(N(i+1)|N(i) ; \beta \right)\cdot f\left(N(1); \beta \right).

\end{eqnarray*}\]

We assume that the initial population size to be known so that \(f\left(N(1);\beta \right) = 1\).

\[\begin{eqnarray*}

\mbox{likelihood} &=& \prod_{i=1}^{n} f\left(N(i+1)|N(i) ; \beta \right) \\

&=& \prod_{i=1}^{n}\left[\frac{1}{\sqrt[]{2\pi}\sigma_e^2 N(i)} e^{-\frac{\left\lbrace N(i+1)-N(i)- r_m N(i)\left[1-\left( \frac{N(i)}{K}\right)^{\theta} \right]\right\rbrace^2} {2\sigma_e^2 N(i)^2}}\right]\\

&=&\prod_{i=1}^{n} \left[\frac{1}{\sqrt[]{2\pi}\sigma_e^2 N(i)} e^{{-\frac{1}{2\sigma_e^2}\left\lbrace \frac{N(i+1)-N(i)}{N(i)}-r_m\left[1-\left( \frac{N(i)}{K}\right)^{\theta}\right] \right\rbrace}^{\theta} }\right]\\

&=& \frac{1}{(\sqrt[]{2\pi})^n}\frac{1}{(\sigma_e)^n}\frac{1}{\prod_{i=1}^{n} N(i)} e^{-\frac{1}{2\sigma_e^2}\sum_{i=1}^{n}\left\lbrace R(i)- r_m\left[1-\left( \frac{N(i)}{K}\right)^{\theta}\right] \right\rbrace^2}.

\end{eqnarray*}\]

The log-likelihood can be given as,

\[\begin{equation}

\mbox{log-likelihood} = -\frac{n}{2}\log(2\pi)-\frac{n}{2}\log(\sigma_e^2)-\sum_{i=1}^{n}\log(N(i))-\frac{1}{2\sigma_e^2}\sum_{i=1}^{n}\left\lbrace R(i)- r_m\left[1-\left( \frac{N(i)}{K}\right)^{\theta}\right] \right\rbrace^2.

\end{equation}\]

To compute the conditional posterior following process has been carried out,

\[\begin{eqnarray*}

f(r_m|\theta,K,\sigma_e^2,\boldsymbol{N})&=&\frac{f(\boldsymbol{N},r_m,\theta,K,\sigma_e^2)}{f(\theta,K,\sigma_e^2,\boldsymbol{N})}\\

&=& \frac{f(\boldsymbol{N}|r_m,\theta,K,\sigma_e^2)\cdot f(r_m,\theta,K,\sigma_e^2)}{f(\boldsymbol{N},\theta,K,\sigma_e^2)}\\

&=&\frac{f(\boldsymbol{N}|r_m,\theta,K,\sigma_e^2)\cdot\pi(r_m)\pi(\theta)\pi(K)\pi(\sigma_e^2)}{f(\boldsymbol{N}|\theta,K,\sigma_e^2)\cdot f(\theta,K,\sigma_e^2)}\\

&=&\frac{f(\boldsymbol{N}|r_m,\theta,K,\sigma_e^2)\cdot \pi(r_m)\cdot \pi(\theta)\cdot \pi(K)\cdot\pi(\sigma_e^2)}{f(\boldsymbol{N}|\theta,K,\sigma_e^2)\cdot \pi(\theta)\cdot \pi(K)\cdot\pi(\sigma_e^2)}\\

&=&\frac{f(\boldsymbol{N}|r_m,\theta,K,\sigma_e^2)\cdot \pi(r_m)}{f(\boldsymbol{N}|\theta,K,\sigma_e^2)}.

\end{eqnarray*}\] Let \(m=f(\boldsymbol{N}|\theta,K,\sigma_e^2)\), be the joint marginal probability density function of the data. \[\begin{eqnarray}

f(r_m|\theta,K,\sigma_e^2,\boldsymbol{N}) &\propto& f(\boldsymbol{N}|r_m,\theta,K,\sigma_e^2)\cdot \pi(r_m) \notag\\

&\propto& \prod_{i=1}^{n} f(N_{i+1}|N_i ; r_m,\theta,K,\sigma_e^2)\cdot \pi(r_m).

\end{eqnarray}\] Similarly,

\[\begin{eqnarray}

f(\theta|r_m,K,\sigma_e^2,\boldsymbol{N})&\propto& \prod_{i=1}^{n} f(N_{i+1}|N_i ; r_m,\theta,K,\sigma_e^2)\cdot \pi(\theta)\\

f(K|r_m,\theta,\sigma_e^2,\boldsymbol{N})&\propto& \prod_{i=1}^{n} f(N_{i+1}|N_i ; r_m,\theta,K,\sigma_e^2)\cdot \pi(K)\\

f(\sigma_e^2|r_m,\theta,K,\boldsymbol{N}) &\propto& \prod_{i=1}^{n} f(N_{i+1}|N_i ; r_m,\theta,K,\sigma_e^2)\cdot \pi(\sigma_e^2).

\end{eqnarray}\]

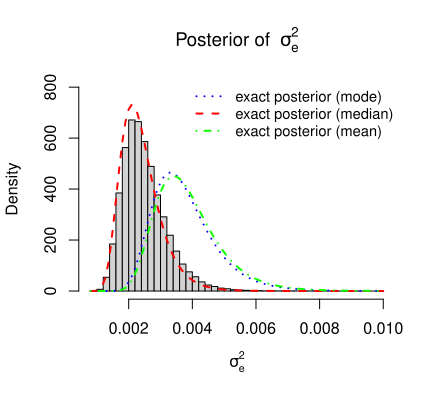

In Bayesian linear regression we already verify that the variance (specially \(\phi\)) after observed data follows \(\mathcal{IG}\left( \mbox{shape} = \alpha+\frac{n}{2}, \mbox{rate} =\frac{1}{2} \sum_{i=1}^{n}\left(y_i-\beta_0-\beta_1x_i\right)^2 + \gamma\right)\). Similarly here we expect posterior distribution of variance(\(\sigma_e^2\)) as follows:

\[\begin{equation}\label{eq:post_sigma_sq}

\sigma_e^2|\boldsymbol{N} \sim \mathcal{IG}\left( \mbox{shape} = \alpha_2 +\frac{n}{2}, \mbox{rate} =\frac{1}{2}\sum_{i=1}^{n}\left(y_i- r_m \left\lbrace 1-\left( \frac{N(t)}{K}\right)^{\theta} \right\rbrace\right)^2+\beta_2\right).

\end{equation}\]

If the prior distribution \(\pi(r_m)\) is considered to be \(\mbox{gammma}(\alpha, \beta)\) which takes only positive values, then task of estimation of a declining population may be underestimated.

To reduce the computational time a correct choice of priors is required. In this case, since \(K\) is a property of the environment, it should not change drastically. Posterior sample of k should not vary too much away from the prior mean of \(K\).

If the prior distribution \(\pi(r_m)\) is considered to be \(\text{gamma}(\alpha, \beta)\) which takes only positive values, then the task of estimation of a declining population may be underestimated.

To reduce the computational time, a correct choice of priors is required. In this case, since \(K\) is a property of the environment, it should not change drastically. The posterior sample of \(K\) should not vary too much from the prior mean of \(K\).

The above structure of the posterior density function of \(\sigma_e^2\) given in the equation \(\eqref{eq:post_sigma_sq}\) is verified by the simulation for the simulated data.